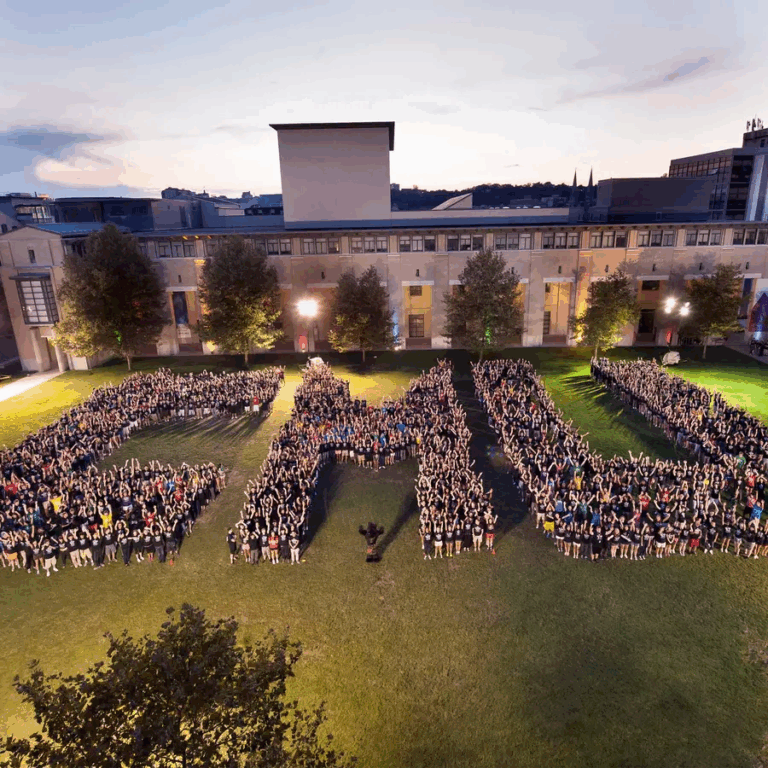

Why Do So Many CMU Grads Have an Inferiority Complex?

Asked on Quora years ago; I’ve cross-posted my answer here.

Asked on Quora years ago; I’ve cross-posted my answer here.

Packrafting is simple. You carry all of your kit, to the edge of the water, and make the transition.

Late last week, a few of us started discussing ways we could help out local restaurants that are devastated by the COVID crisis. My friend Michelle came up with the brilliant idea to raise money to buy gratitude meals for first responders, to help express just some of our thanks for the work they’re doing and…

At this writing in Seattle, amid the COVID-19 outbreak, nearly all schools have announced closure, and have gone (or are soon going) to remote learning. Many workplaces have also done the same, and public officials are encouraging people not to gather in large groups. First, please read this excellent summary from Tomas Pueyo as to…

Flipping channels today on CNN, MSNBC and elsewhere I’m reminded of a famous book in social psychology. Social Psychologist Leon Festinger, the same researcher who coined “cognitive dissonance,” released a fascinating book in 1956 called When Prophecy Fails. When prophecies fail, the most fervent believers often double-down on their original beliefs, asserting that their very…

I’m working on a neural-style transfer project, and have several machine learning models trained to render input photos in particularly styles. The current set is below; input image on the left, output image on the right, with model name in lower right hand corner. I’ve got a few clear favorites, but I’d love to see…

I’ve always been fascinated by past visions of the future. Science fiction uses the future to tell us something about ourselves, so looking back on past visions of the future, we can learn something about that age and the values, myopia, optimism and fears of the time. It’s also healthy to continually do cross-checks on “how…

In 2015, a research paper by Gatys, Ecker and Bethge posited that you could use a deep neural network to apply the artistic style of a painting to an existing image and get amazing results, as though the artist had rendered the image in question. Soon after, a terrific and fun app was released to the…

They say that a fan tells 3 people about great service, and someone who has received poor service tells 10. Well, I’m pissed at Amy Schumer’s tour company and I’m pissed at ticket reseller Viagogo for being very scammy. I’d like to shift gears from the usual topics on this nascent blog (tech, data analysis,…

I’m on a parent advisory committee at my daughter’s school. The committee is taking a look at the school’s existing Computational Thinking curriculum and where it might want to head in the future. Luckily for us, the faculty is already doing a very good job with the curriculum. So our role as advisers is to provide a…

You must be logged in to post a comment.